Prelude to War: 3. Blood and Conspiracy: The Republic Under Siege

Political Murders and Putsch Attempts (1919-1923)

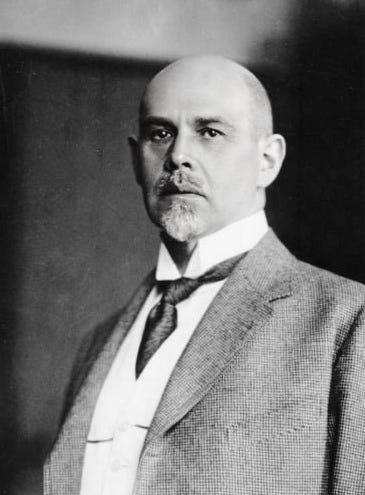

On 26 August 1921, Matthias Erzberger was walking through the Black Forest near the town of Bad Griesbach in southwestern Germany. He was on holiday with a friend, taking a break from his work as a Reichstag deputy and former Reich Minister of Finance. Two men approached them on the forest path. Without warning, they drew pistols and opened fire. Erzberger fell, wounded. As he lay on the ground, one of the assassins walked up and shot him multiple times at close range. Erzberger died instantly. His killers fled across the border into Hungary, where authorities refused German extradition requests.

Matthias Erzberger was forty-five years old. He had been a prominent politician in the Catholic Centre Party, one of the major political parties in Germany, which represented Catholic interests in a country where Protestants outnumbered Catholics roughly two to one. Erzberger had served in various government positions during the First World War. In November 1918, when Germany’s military leadership informed the government that the war was lost and an immediate armistice was necessary, they refused to participate in surrender negotiations themselves. The task fell to Erzberger, a civilian with no military background. He led the German delegation that signed the armistice in Ferdinand Foch’s railway carriage at Compiègne on 11 November 1918.

This made Erzberger a target. In the mythology that developed among German nationalists after the war, Germany had not been defeated militarily but had been betrayed by politicians who signed an unnecessary surrender. Erzberger, as the man who literally signed the armistice document, became a symbol of this supposed betrayal. Nationalist newspapers attacked him relentlessly. Right-wing politicians denounced him in speeches. Extremist groups published lists identifying him and others as traitors who deserved death.

Erzberger had also supported the Treaty of Versailles. When the treaty terms arrived in May 1919, most Germans across the political spectrum found them devastating. The treaty required Germany to accept sole responsibility for causing the war, pay massive reparations, reduce its army to 100,000 men, surrender territory to France and Poland, and submit to Allied occupation of the Rhineland. Many Germans wanted the government to reject the treaty regardless of consequences. Erzberger argued that rejection would lead to Allied invasion and even harsher terms. He voted to accept the treaty. This made him, in the eyes of extreme nationalists, doubly guilty of treason.

His assassins were Heinrich Tillessen and Heinrich Schulz, former naval officers who belonged to Organisation Consul, a secret right-wing paramilitary group dedicated to killing politicians it considered traitors. The organisation operated with a clear structure, leadership, and a specific target list. Members received orders, carried out assassinations, and escaped through established networks that moved them across borders and provided them with false documents and protection. German courts, staffed largely by judges who shared nationalist sympathies, handed down lenient sentences when assassins were caught and often accepted claims of patriotic motivation as mitigation.

Erzberger was not the first target. In February 1919, Kurt Eisner, the leader of Bavaria’s revolutionary government, was shot and killed in Munich by a young aristocrat named Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley. Eisner had led the socialist revolution that overthrew Bavaria’s monarchy in November 1918 and declared Bavaria a republic. He was Jewish, socialist, and a pacifist who had opposed the war. His assassin walked up to him on a Munich street and shot him in the back of the head. Graf von Arco was arrested, tried, and initially sentenced to death, but the sentence was commuted and he served only a few years in prison.

The pattern was consistent. Right-wing assassins targeted politicians associated with the armistice, the Versailles Treaty, the revolution, or left-wing politics. The killers belonged to paramilitary organisations, often former military officers who had fought in the war and joined Freikorps units afterwards. They received support from broader networks of nationalist sympathisers. When caught, they received sympathetic treatment from courts and often served minimal sentences or escaped punishment entirely.

Rathenau’s Murder

On 24 June 1922, Walther Rathenau was driven through Berlin in an open car, travelling from his home to the Foreign Ministry where he served as Foreign Minister. It was a Saturday morning. As Rathenau’s car slowed to take a corner in the Grunewald district, a large Mercedes pulled alongside. Three men were inside. One stood and fired a machine pistol at Rathenau, hitting him multiple times. Another threw a hand grenade into Rathenau’s car. The Mercedes sped away. Rathenau died within minutes.

Walther Rathenau was fifty-four years old, one of Germany’s most prominent industrialists and intellectuals. His father, Emil Rathenau, had founded AEG, one of Germany’s largest electrical engineering companies, which manufactured everything from light bulbs to locomotives. Walther took control of the company after his father’s death and expanded it further. He was wealthy, sophisticated, multilingual, and connected to Germany’s cultural and intellectual elite. He wrote books on philosophy, economics, and politics. He had served during the war organising Germany’s raw materials distribution, a crucial role that kept German industry functioning despite the Allied blockade.

After the war, Rathenau entered government service. He believed Germany must accept its defeat, fulfil its obligations under the Versailles Treaty, and rebuild relationships with the Allies, particularly France. As Foreign Minister, he negotiated the Treaty of Rapallo with Soviet Russia in April 1922, a diplomatic breakthrough that re-established relations between Germany and Russia and demonstrated that Germany, despite its weakened position, could still conduct independent foreign policy. This achievement earned him respect internationally but intensified hatred from German nationalists who viewed any cooperation with the Soviet Union as Bolshevik collaboration.

Rathenau was also Jewish. This made him particularly vulnerable to the antisemitic hatred that pervaded right-wing nationalist circles. Antisemitism had existed in Germany before the war, but defeat, revolution, and economic hardship intensified it dramatically. Conspiracy theories blamed Jews for Germany’s defeat, the revolution, the Versailles Treaty, and the Republic itself. Nationalist propaganda portrayed Jews as alien elements who controlled Germany’s economy and government for their own benefit while betraying German national interests. Rathenau, wealthy and prominent, Jewish and serving as Foreign Minister, embodied everything these conspiracy theories claimed to expose.

His assassins were Erwin Kern and Hermann Fischer, both former naval officers in their early twenties, and Ernst Werner Techow, who drove the car. All three belonged to Organisation Consul, the same group that had killed Erzberger. They had selected Rathenau from the organisation’s target list, surveilled his movements, planned the attack carefully, and executed it in broad daylight on a Berlin street.

The assassination provoked mass demonstrations across Germany. Hundreds of thousands of people marched in cities throughout the country supporting the Republic and demanding action against right-wing violence. The Reichstag passed a Law for the Protection of the Republic that banned extremist organisations and strengthened government authority to prosecute political violence. Organisation Consul was outlawed. Police raids followed. Some members were arrested. Others fled abroad.

Kern and Fischer hid in a castle in Thuringia, in central Germany, where sympathisers sheltered them. When police located them several weeks later, a shootout followed. Kern was killed. Fischer shot himself rather than surrender. Techow was captured, tried, and sentenced to fifteen years in prison. He served five years before being released. After his release, he expressed regret for the murder, one of the few right-wing assassins to do so.

Between 1919 and 1922, Organisation Consul and similar groups carried out more than 350 political murders. The vast majority of victims were left-wing politicians, labour organisers, and journalists. A few were moderate conservatives who advocated cooperation with the Republic. The assassinations aimed to destabilise the Weimar Republic by eliminating its supporters and creating an atmosphere of terror that would prevent moderates from participating in democratic politics.

The campaign largely succeeded in its immediate objectives. Politicians who supported the Republic received death threats regularly. Some travelled with armed guards. Others withdrew from public life. The violence demonstrated that defending democracy in Germany could cost your life and that the state lacked either the will or the capacity to protect its defenders.

The Kapp Putsch

On 13 March 1920, Freikorps units marched into Berlin. They wore the distinctive uniforms and insignia of their formations, carried rifles and machine guns, and moved in military formation through the city streets. Their objective was to overthrow the German government.

The Freikorps were paramilitary units formed after the war from returning soldiers who refused to demobilise. The name meant “free corps,” suggesting volunteer formations operating outside the regular army structure. They had played a crucial role in crushing the Spartacist Uprising in January 1919, when revolutionary socialists led by Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht attempted to overthrow the provisional government and establish a soviet republic. The government, led by Social Democrats who lacked military forces of their own, had called on the Freikorps for help. Freikorps units entered Berlin, fought street battles with revolutionary workers, and killed hundreds of people including Luxemburg and Liebknecht themselves, who were murdered after capture.

The Freikorps had operated with government sanction throughout 1919, crushing left-wing uprisings in cities across Germany, fighting communist forces in Bavaria where a short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic had been established, and battling Polish irregular forces in disputed border regions. They attracted men who enjoyed military life, who believed Germany had been betrayed rather than defeated, who despised the Republic and everything it represented, and who were willing to use violence against anyone they considered enemies of the nation.

The Treaty of Versailles required Germany to reduce its army to 100,000 men, prohibit conscription, and disband all paramilitary formations including the Freikorps. The Reichswehr, the name for Germany’s post-war military, began implementing these reductions in early 1920. Many Freikorps members faced the prospect of returning to civilian life with no jobs waiting, no prospects, and a country they believed had betrayed the soldiers who defended it.

Wolfgang Kapp provided the political leadership for the putsch attempt. He was sixty-one years old, a Prussian civil servant and politician who had co-founded the Fatherland Party during the war, a nationalist organisation that demanded Germany fight until total victory regardless of cost. After the war, Kapp became involved in right-wing politics and conspiracies to overthrow the Republic. General Walther von Lüttwitz, commander of military forces in and around Berlin, provided the military component. Lüttwitz opposed the Freikorps reductions and refused government orders to disband units under his command.

On the night of 12-13 March, approximately 5,000 men from the Marinebrigade Ehrhardt, one of the most notorious Freikorps units, began marching toward Berlin. The brigade was named after its commander, Hermann Ehrhardt, a former naval officer who had built it into a disciplined formation that combined military effectiveness with extreme nationalist ideology. His men wore a distinctive swastika symbol on their helmets, not yet associated with Hitler’s movement but already used by various right-wing groups as a symbol of German nationalism and antisemitism.

The government learned of the approaching troops. Friedrich Ebert, the Reich President, and Gustav Noske, the Defence Minister who had previously relied on Freikorps units to crush left-wing uprisings, ordered the Reichswehr to stop them. General Hans von Seeckt, who would soon become the Reichswehr’s commander, responded with words that exposed the Republic’s fundamental weakness: “Reichswehr does not fire on Reichswehr.” German soldiers, he meant, would not fight other German soldiers even to defend the legitimate government.

The Reichswehr’s refusal to intervene left the government defenceless. Ebert and his cabinet fled Berlin during the night, first to Dresden and then to Stuttgart in southern Germany. When the Marinebrigade Ehrhardt entered Berlin the next morning, they encountered no resistance. They occupied government buildings, raised imperial flags, and declared a new government with Kapp as Reich Chancellor and Lüttwitz as commander of the armed forces.

Kapp announced the Weimar Republic was finished. He declared the Versailles Treaty void, promised to restore German honour and power, and called for a government of national unity based on military strength and traditional values. His proclamations were vague on specifics but clear in intent: the democratic experiment had failed and Germany needed authoritarian leadership.

The putsch collapsed within four days. The government, from its exile in Stuttgart, called for a general strike. German trade unions, dominated by Social Democrats and representing millions of workers, organised the response. Workers throughout Germany stopped work. Trains stopped running. Electricity generation ceased in many areas. Government offices shut down. Banks closed. Newspapers stopped publishing. Berlin, without functioning transport or utilities, became paralysed.

Kapp had military force but no administrative capacity. He could occupy government buildings but could not operate a government without the civil servants who refused to recognise his authority. He could issue proclamations but had no way to distribute them widely with newspapers on strike. He held formal power but had no actual control.

The putsch also triggered left-wing uprisings in the Ruhr, Germany’s industrial heartland in the west. Workers there formed armed militias called Red Army units, seized control of cities including Essen and Dortmund, and fought pitched battles with police and remaining government forces. These uprisings terrified moderate Germans who saw Bolshevik revolution spreading. The legitimate government, having defeated the right-wing putsch through a general strike organised by the left, now faced the prospect of losing control to revolutionary workers it had called into action.

Kapp fled Berlin on 17 March. His government had lasted four days. He escaped to Sweden, where he lived in exile until returning to Germany in 1922 after receiving assurances he would face trial rather than summary execution. He died in prison while awaiting trial. Lüttwitz fled to Hungary. Ehrhardt and most of his men escaped to Bavaria, where the regional government protected them from prosecution.

The general strike ended, but fighting in the Ruhr continued. The Reichswehr and Freikorps units entered the region and crushed the Red Army units over several weeks of brutal combat. Hundreds of workers were killed in the fighting and its aftermath. The Republic had survived challenges from both right and left, but the cost was measured in dead Germans killed by other Germans, a government that had fled its capital, and a military that had demonstrated it would not defend democracy if doing so required fighting other military men.

The Beer Hall Putsch

On the evening of 8 November 1923, approximately 3,000 people gathered in the Bürgerbräukeller, a large beer hall in Munich, the capital of Bavaria in southern Germany. They had come to hear a speech by Gustav von Kahr, Bavaria’s State Commissioner, who held near-dictatorial powers in the region. The hall was full, warm, and noisy with conversation and the sound of beer steins on tables. At around 8:30, a group of armed men forced their way into the hall. Some wore military uniforms. Their leader was Adolf Hitler.

Adolf Hitler was thirty-four years old in 1923. He had served in the German Army during the war, fighting on the Western Front as a dispatch runner, a dangerous job that involved carrying messages between command posts and front-line positions. He had been wounded twice and received the Iron Cross Second Class and, unusually for someone of his enlisted rank, the Iron Cross First Class, a decoration normally reserved for officers. He believed Germany had been on the verge of victory when politicians betrayed the army by signing the armistice. After the war, he remained in Munich, where he became involved in right-wing politics. He joined a small nationalist party that would become the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, abbreviated as NSDAP but commonly called the Nazi Party. Through force of personality, oratorical skill, and political manoeuvring, he had made himself the party’s leader.

Hitler believed Germany was controlled by Jews, communists, and weak liberals who had stabbed the army in the back, signed the shameful Versailles Treaty, and were now allowing Germany to be destroyed from within. He advocated racial nationalism, antisemitism, and violent opposition to communism and democracy. The Nazi Party remained small, with perhaps 20,000 members concentrated mainly in Bavaria, but it had grown rapidly through Hitler’s speeches, which attracted crowds of hundreds or thousands who responded to his message that Germany had been betrayed and that only ruthless nationalist leadership could restore German power.

Hitler had organised armed formations to support the party. The Sturmabteilung, the Storm Division, usually abbreviated as SA, served as the party’s paramilitary wing. These stormtroopers wore brown shirts and military-style uniforms, carried clubs and sometimes weapons, and provided security at Nazi meetings while disrupting opponents’ gatherings. The SA attracted unemployed veterans, young men seeking action and purpose, and those drawn to the combination of military camaraderie and political violence. Ernst Röhm, a former army officer who had helped organise and arm the Freikorps in 1919, commanded the SA and provided crucial connections to military and paramilitary circles. Hitler also maintained a smaller, more disciplined unit called the Stoßtrupp-Hitler, the Hitler Shock Troop, which served as his personal bodyguard and included some of his most devoted followers.

On that November evening in the Bürgerbräukeller, Hitler intended to force Bavaria’s leaders to support a national revolution. He jumped onto a table, fired a pistol into the ceiling to get attention, and announced that the national revolution had begun. His men sealed the exits. Hitler demanded that Kahr, along with the commander of Bavaria’s military forces and the head of the Bavarian police, all of whom were in the hall, join him in overthrowing the Weimar government in Berlin and establishing a new nationalist regime. He took them to a private room and, with a combination of threats and persuasion, extracted agreements to support the putsch.

Hitler had organised a paramilitary wing called the Sturmabteilung, the Storm Division, usually abbreviated as SA. These were the party’s stormtroopers, men who wore brown shirts and military-style uniforms, carried clubs and sometimes weapons, and provided security at Nazi meetings while disrupting opponents’ gatherings. The SA attracted unemployed veterans, young men seeking action and purpose, and those drawn to the combination of military camaraderie and political violence. Ernst Röhm, a former army officer who had helped organise and arm the Freikorps in 1919, commanded the SA and provided crucial connections to military and paramilitary circles.

Hitler believed he was replicating the march on Rome that had brought Benito Mussolini to power in Italy the previous year. He expected the Bavarian authorities, once committed, would mobilise their forces and march on Berlin to overthrow the Republic. He told the crowd in the beer hall that he had the support of General Erich Ludendorff, the former First Quartermaster General who had effectively commanded German military operations during the later stages of the war. Ludendorff, retired and living near Munich, had become involved with various right-wing conspiracies. He appeared at the beer hall that evening, lending his prestige to Hitler’s attempt.

After securing these commitments, Hitler released Kahr and the others. This proved a fatal mistake. Once free from the immediate threat of SA guns, Kahr contacted Munich’s military garrison and police forces and ordered them to suppress the putsch. He issued statements declaring Hitler a traitor and denouncing the attempted coup.

The next morning, 9 November, Hitler led approximately 2,000 SA men and supporters on a march through Munich toward the War Ministry. They intended to rally support, demonstrate popular backing for the national revolution, and confront authorities with a mass movement that would force capitulation. As they marched through central Munich, they encountered a police cordon blocking the street. What happened next remains disputed in details but clear in outcome. Someone fired. Whether the first shot came from police or from the marchers has never been definitively established. A firefight followed. Sixteen putschists were killed along with four police officers. Others were wounded. The column broke and scattered. Hitler fell or was pulled to the ground and dislocated his shoulder. He fled the scene.

The putsch collapsed completely. Police arrested Hitler two days later at the home of a supporter outside Munich. They arrested Ludendorff, who had remained at the scene after the shooting and been taken into custody. They arrested Röhm and other Nazi leaders. The Nazi Party was banned. The SA was dissolved. The national revolution had lasted roughly twelve hours and ended with dead men in the street and the movement’s leaders in prison awaiting trial.

Hitler’s Trial

The trial began on 26 February 1924 in a Munich courtroom. Hitler faced charges of treason, which carried a potential death sentence or life imprisonment. He used the trial as a platform. German law allowed defendants extensive opportunity to speak, and Hitler transformed his defence into a sustained attack on the Republic and a declaration of his political philosophy.

He admitted organising the putsch but denied it was treason. Real treason, he argued, had been committed by the November Criminals who signed the armistice and betrayed Germany in 1918, by the politicians who accepted the Versailles Treaty, and by the weak republican government that allowed communists and Jews to destroy Germany from within. His action had been patriotic resistance against these traitors. He portrayed himself as a German nationalist fighting to save the country from its internal enemies.

The judges, all of whom were conservative nationalists appointed during the imperial era or its immediate aftermath, proved sympathetic. They allowed Hitler to speak at length. They permitted him to question prosecution witnesses aggressively. They prevented prosecutors from fully developing their case. The trial received massive newspaper coverage throughout Germany. Hitler’s speeches were reported verbatim. He reached a far larger audience from the courtroom than he ever had from the beer hall stage.

On 1 April 1924, the court found Hitler guilty of treason but delivered the minimum sentence: five years imprisonment with eligibility for parole after serving six months. The judges cited his patriotic motives, his war service, and his sincere belief that he was acting in Germany’s interests. They specifically noted his Iron Cross as evidence of his German loyalty. Ludendorff was acquitted entirely. The court accepted his claim that as a distinguished military leader, he could not have known he was participating in treason and must have been misled by others.

Hitler entered Landsberg Prison, located about 65 kilometres west of Munich, in April 1924. The conditions were comfortable. He received visitors, conducted extensive correspondence, and was treated with considerable deference by guards and prison officials who viewed him as a political prisoner rather than a common criminal. He used the time to write. With help from Rudolf Hess, an early Nazi Party member who had participated in the putsch and was imprisoned alongside him, Hitler produced a book outlining his worldview and political programme. The book would be published as Mein Kampf, My Struggle.

Hitler served only nine months before receiving parole on 20 December 1924. He emerged from prison with several advantages he had lacked before the putsch. He was nationally known rather than regionally obscure. His trial speeches had been published throughout Germany and read by millions. He had written a book that would serve as the Nazi movement’s foundational text. He had learned that attempting to seize power by force was premature and that the Nazi Party must achieve power through legal means, by winning elections and manipulating the democratic system from within.

The Beer Hall Putsch had failed, but its failure proved instructive. Hitler would not attempt another armed uprising. Instead, he would rebuild the Nazi Party as an electoral organisation that combined violent intimidation with sophisticated propaganda, that attracted support from Germans who feared communism and resented the Versailles Treaty, and that presented itself as the only force capable of restoring German greatness. The putsch marked not the end of Hitler’s political career but its true beginning.

The Psychology of Violence

The political violence that consumed Germany between 1919 and 1923 followed patterns that were neither random nor spontaneous. The assassinations, the putsch attempts, and the street fighting emerged from specific conditions created by defeat, revolution, and the Republic’s establishment. Understanding these patterns explains how a democratic system could coexist with systematic political murder and armed rebellion against its authority.

The military’s attitude toward the Republic was fundamental. German military culture emphasised honour, obedience to superiors, and national service. Officers came predominantly from aristocratic families or the upper middle class. They viewed themselves as guardians of German national interests above politics. The war’s end shattered this worldview. The military leadership had assured the Kaiser and the government that Germany would win. When victory proved impossible, they shifted responsibility to politicians. General Ludendorff and Field Marshal Hindenburg, Germany’s senior commanders, informed the government in late September 1918 that an immediate armistice was necessary because military collapse was imminent. Within weeks, they were claiming Germany had been on the verge of victory when treasonous politicians sued for peace.

This narrative, the “stab in the back” myth, became central to right-wing political thought. Germany’s army, undefeated in the field according to this mythology, had been betrayed by socialists, Jews, and weak liberals on the home front who undermined morale, fomented revolution, and pressured the military to accept surrender. The myth was false. Germany’s army had suffered defeats throughout 1918, its allies were collapsing, the home front was starving due to the Allied blockade, and military commanders themselves had demanded the armistice. But the myth served crucial psychological functions. It preserved military honour, explained defeat without acknowledging failure, and identified internal enemies who had supposedly caused Germany’s collapse.

Officers and enlisted men who accepted this narrative had fought for four years, watched comrades die, suffered privation and danger, and returned home expecting gratitude and recognition. Instead they found revolution, the Kaiser gone, the monarchy abolished, socialists in power, and Germany treated as a defeated criminal nation forced to accept harsh peace terms. Many concluded that the war’s sacrifices had been betrayed by those who now governed Germany.

The Freikorps channelled these grievances into organised violence. These units provided military camaraderie, purpose, and action for men who could not or would not adjust to civilian life. They offered regular pay when jobs were scarce, status and authority when traditional hierarchies had collapsed, and the satisfaction of fighting enemies: communists, Poles, revolutionary workers who could be blamed for Germany’s humiliation. The government’s decision to employ Freikorps units against left-wing uprisings legitimised their violence and established the precedent that the Republic would tolerate and even support paramilitary forces when they served immediate state interests.

This created a fundamental contradiction. The Republic relied on men who despised it to defend it against revolutionaries who wanted to overthrow it from the left. Neither the Freikorps nor the regular military felt loyalty to democratic institutions. They cooperated with the Republic when doing so aligned with their interests, particularly when it meant fighting communists. But when the Kapp Putsch demonstrated conflict between military solidarity and democratic legitimacy, General von Seeckt’s statement that Reichswehr would not fire on Reichswehr revealed where ultimate loyalties lay.

The judiciary’s behaviour reinforced this pattern. Judges in Germany were civil servants appointed for life, trained under the Empire and generally conservative in outlook. They viewed left-wing violence as revolutionary criminality threatening civilisation itself. They viewed right-wing violence as misguided patriotism. Statistics compiled by a judicial reform commission in 1924 documented the disparity. The commission examined political murders committed between 1919 and 1922. Of 354 murders committed by right-wing perpetrators, 326 went unsolved or unpunished. Twenty-four resulted in convictions. The average sentence for those convicted was four months. Of 22 murders committed by left-wing perpetrators, 17 resulted in convictions. Ten defendants received death sentences. The average sentence for those not executed was fifteen years.

This bias demonstrated that Germany’s legal system treated attacks on the Republic as less serious than attacks by revolutionaries attempting to overthrow it. The courts implicitly accepted the argument that right-wing violence, while illegal, stemmed from patriotic motives and frustration with a government that had betrayed Germany. This judicial tolerance encouraged further violence by demonstrating that assassinating republican politicians carried minimal risk.

The assassination campaign against the Republic’s supporters achieved its objective of creating terror. Politicians who might have defended democratic institutions concluded the cost was too high. Some withdrew from public life. Others moderated their positions to avoid becoming targets. The cumulative effect was a political culture where defending the Republic required physical courage and willingness to risk assassination, while attacking it incurred little cost and could advance one’s career in right-wing political circles.

The violence also radicalised German political culture. Street fighting between Nazi SA men and communist paramilitaries became routine in German cities during the 1920s. Political meetings required armed guards. Demonstrations regularly turned violent. Citizens became accustomed to political violence as a normal feature of public life. This normalisation of violence eroded the distinction between legitimate political opposition and armed rebellion.

Middle-class Germans, who might have formed the Republic’s core support, increasingly viewed violence from both extremes as equally threatening. They feared communist revolution and working-class militancy but also found Nazi stormtroopers and nationalist assassination squads disturbing. Many concluded that the Republic could not maintain order and that Germany needed stronger leadership. This attitude would prove decisive when economic crisis struck later in the decade and Germans faced a choice between defending democracy or accepting dictatorship in exchange for promises of stability.

The Republic survived the crisis years of 1919 to 1923, but survival came at enormous cost. Its defenders had been assassinated. Its military had demonstrated conditional loyalty at best. Its courts had shown they would not punish the Republic’s enemies with the same severity they applied to its defenders. The paramilitary culture established during these years would persist, evolving into the SA’s mass membership and providing the foundation for organised political violence on an unprecedented scale. The lesson learned by Hitler and others was not that armed rebellion against democracy was wrong but that it was premature and that power must be achieved through legal means before being used to destroy the legal system that granted it.